Clearing the air: Ordinary citizens uncover toxic truths near waste incinerators

MANILA, Philippines —A group of ordinary citizens in Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental spent weeks carrying palm-sized devices, quietly gathering evidence of something they could already see and feel: the thick haze drifting from a controversial waste facility in their neighborhood.

In their homes, in small stores, and along busy roads, volunteers from all walks of life—storekeepers, students, waste workers—watched as the monitors blinked, counted, and recorded.

They weren’t scientists, but their mission was scientific: capture, for the first time, hard data about what happens to the air they breathe when waste is burned just down the road.

They were not alone. Across Surabaya, Indonesia and Ogijo, Nigeria, parallel teams of local volunteers joined the world’s first cross-regional, citizen-powered study of air quality near waste incineration plants in the Global South.

Their findings cut through political promises and technical jargon to reveal a simple, troubling reality: waste burning is leaving a measurable mark on local air and people’s health.

This story is Part 1 of a two-part INQUIRER.net report on Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives’ (GAIA) Air Quality Monitoring (AQM) initiative, based on the recently released study “Clearing the Air: The Truth Behind Waste Incineration.”

Part 1 details the findings from the Philippines, Indonesia, and Nigeria; Part 2 will examine how communities are fighting back and the global forces driving waste incineration in the Global South.

The hidden threat: What’s really in the air

Most people in these communities know the scent of burning waste, the itch in their throats, the sting in their eyes. But what lingers is often invisible—fine particles called particulate matter (PM), especially PM2.5, which can slip deep into the lungs and even cross into the bloodstream.

Just how small are these particles? PM10, PM2.5, and PM1 are many times smaller than the thickness of a human hair, which is about 50 to 70 micrometers wide. These particles are so tiny that they can pass through our body’s natural defenses and reach even our internal organs.

As the international zero waste advocacy group GAIA—which wrote and published the study findings—explained:

“Because it is so small, particulate matter can easily permeate every organ in the body, with disastrous consequences on human health.”

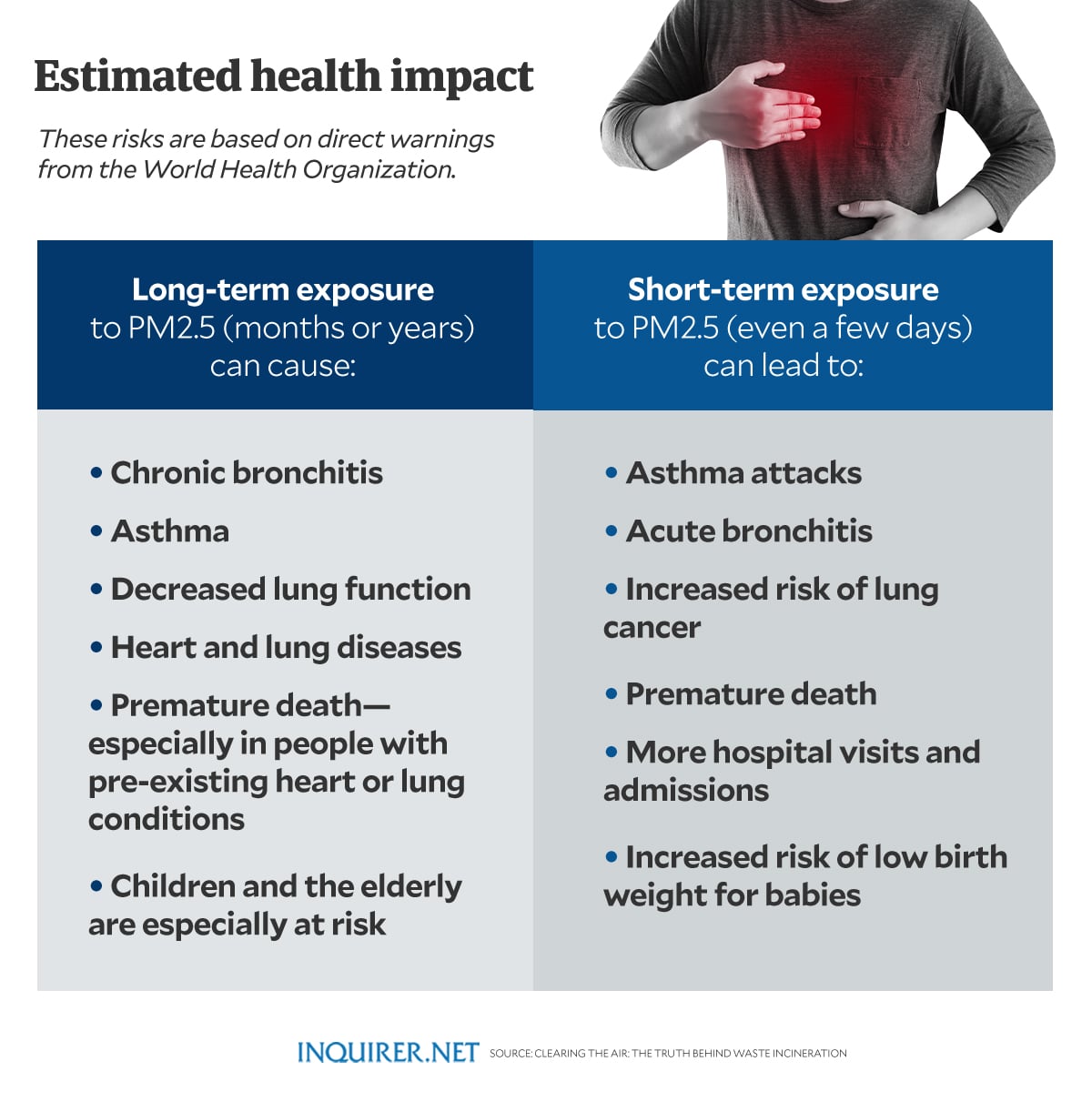

And the consequences are not just distant possibilities; they play out in real lives, in both the long term and the short term. As GAIA warns in the study:

“Long-term exposures can cause respiratory and cardiovascular problems such as coughing, difficulty breathing, decreased lung function, chronic bronchitis, asthma, and premature death among people with heart or lung diseases. Children and the elderly are especially vulnerable.”

But even short encounters with high levels of PM2.5 are risky:

“Short-term exposures to PM2.5 have been associated with premature death, acute bronchitis, asthma attacks, increased hospitalization, increased risk of low birth weight, and increased risk of lung cancer.”

READ: Waste-to-energy: The perils for human health, environment

The World Health Organization (WHO) has set its “safe” limit for PM2.5 at just 15 micrograms per cubic meter, and only for a few days a year. But in Dumaguete, Surabaya, and Ogijo, ordinary days were anything but safe.

Dumaguete’s fight for clean air and survival

Dumaguete is famous for its prominent educational institutions and its breathtakingly beautiful waterfront, but for months, its headlines were made by something else: a pyrolysis-gasification plant with no known safeguards built right beside the city’s central waste facility.

READ: Study shows Dumaguete‘s famed waterfront extremely polluted

Most people didn’t even know it was operating until a plume of smoke was caught on video.

“Our concern was especially for the pollutants that you can’t see with the naked eye,” said Dr. Jorge Emmanuel, chief technical advisor for the project and adjunct professor at Silliman University.

He and other scientists, working with GAIA and War on Waste Negros, recruited 17 community volunteers—including mothers, store owners, and waste workers—to wear monitors during their daily routines.

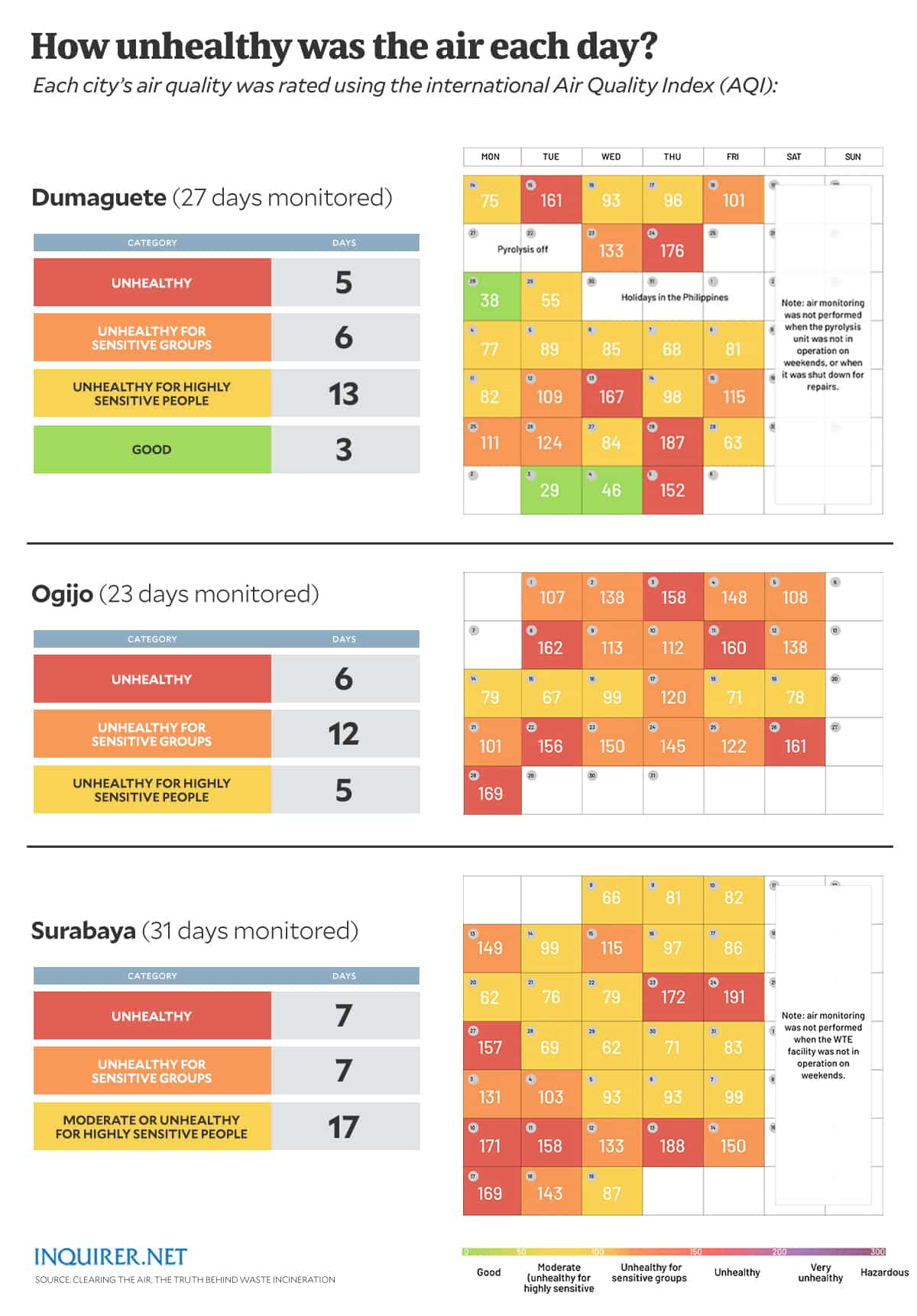

The volunteers recorded PM2.5 levels as high as 106 micrograms per cubic meter—seven times the WHO’s safe limit. The results were not just troubling, they were relentless. During 27 days of air monitoring in Dumaguete, the air was dangerously polluted for 23 days, far above the safe limit set by the WHO.

To put that in perspective, the WHO states that communities should not experience more than four days of this kind of pollution in a whole year. In Dumaguete, people were exposed to unsafe air nearly every single day the monitors were worn—an 85 percent exceedance rate, and a level of risk far beyond what any community should face.

The study stressed that the health risks faced by residents went far beyond mere discomfort. According to the team’s health risk assessment, air pollution from the facility could cause up to 179 premature deaths each year if the plant continues to operate unchecked.

“[We] have been requesting the city and the government agencies involved for copies of the stock test emissions because we know of the many pollutants that come from these types of technologies,” Dr. Emmanuel said, referring to the pyrolysis-gasification machine.

“In one forum, we found out that no tests have been done, and at least to this date, no test results have ever been released,” he emphasized. Dr. Emmanuel added that even members of the research team and city councilors themselves were denied entry to the facility.

The monitoring sites included schools, homes, and small stores, making it clear: pollution here doesn’t respect property lines. It travels, settles, and clings to everyday life.

Pollution doesn’t respect boundaries

For Aloja Santos, one of the community volunteers in the air monitoring project, the real danger is both what you breathe and what you eat.

“Behind the central MRF (materials recovery facility), mountains of trash are dumped, and water filtering through the waste can become contaminated,” Santos explained.

“Nearby rivers connect to the ocean, where locals fish for their livelihood. That seafood eventually ends up on our plates. The question stands: Does this benefit us, or does this only pose danger to our health?”

Barangay Candau-ay resident Rochelle Gille Noala doesn’t mince words about what she sees every day.

“This is not an MRF, the reality is this is a dumpsite, that’s the truth. This causes a multitude of effects, especially on the health of our children. My children have been suffering from non-stop cough because of the pollution in the air here at the so-called MRF at Candau-ay, which is a blatant dumpsite,” Noala said.

Her worry only grows as the rainy season arrives: “What are we going to do when the calamities arrive, especially a flood? All the garbage from Candau-ay will come back to us, the people here in Dumaguete.”

But the risks aren’t limited to the air. The study found that inside the pyrolysis facility, plastic waste is melted without proper ventilation to protect workers from toxic fumes.

Even more concerning, the ash from the pyrolysis unit is reportedly mixed into cement hollow blocks, with no testing for dangerous substances such as dioxins, heavy metals, or other contaminants—nor any treatment to stabilize or neutralize what might be inside.

Surabaya: When every day is a bad air day

Across the sea in Surabaya, Indonesia’s second-largest city, volunteers faced a similar challenge near the Benowo Waste-to-Energy (WTE) Power Plant.

The plant is supposed to be a symbol of modern waste management, but for the people in Sumberejo Urban Village, it’s become a source of black smoke and bitter smells.

Al Tubongbanua, one of the technical leads, recounted how air quality monitors revealed “maximum daily average of PM2.5 concentration levels [reached as high as] 113 micrograms per cubic meter across all 14 monitors”—eight times the WHO standard.

During 31 days of monitoring, there wasn’t a single “good” air day.

Seven days out of 31, the air was rated “unhealthy for all” based on US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) criteria; on the other days, it was still dangerous for children, elderly people, or anyone with asthma.

What made the situation even more alarming was the behavior of two types of pollution the study tracked: PM2.5 and PM10. PM10 refers to slightly larger particles—ten micrometers or less in diameter, still invisible to the naked eye, but big enough to cause health problems when breathed in.

While PM10 levels would suddenly spike when people walked past the incinerator—sometimes for just a few minutes or up to an hour—PM2.5 levels tended to stay high for much longer. Unlike PM10, which settles out of the air more quickly, PM2.5 can remain suspended and travel long distances, spreading pollution from the plant to residential areas, main roads, markets, and even schools nearby.

“The air pollution from these incinerators [is] not just a distant threat—they’re already affecting our health and daily lives,” states Wahyu Eka Setyawan of WALHI East Java, Indonesia.

“People are coughing, struggling to breathe, and living in fear of what they can’t see but can certainly feel,” Setyawan added.

For Setyawan and other local leaders, the greatest danger isn’t just the pollution, but the silence surrounding it.

“What’s worse, we’ve been kept in the dark. There’s no transparency, no real space for public participation in decisions that affect our future. This is not just unfair—it’s dangerous,” he said.

“We urgently call on governments to cancel these waste-to-energy projects and start listening to the people who are paying the price with their lungs.”

The community’s demand is simple but bold: shut the plant down, investigate the health impacts, and shift to solutions that don’t leave neighborhoods gasping for breath.

Ogijo: Breathing becomes a gamble

In Ogijo, Nigeria, the threat arrived in the form of a tire “recycling” facility. Officially, it’s a pyrolysis plant, but residents described open burning of tires, and clouds of smoke so thick that some mornings you can’t see past the market stalls.

For three women working at a nearby market, the decision to carry air monitors was about survival, not science.

Every day of the 23-day monitoring period, the PM2.5 levels exceeded the WHO’s guideline, sometimes reaching as high as 82 micrograms per cubic meter. “The smoke… It’s too much. They are polluting everywhere. We have been dealing with this for the past three years. It’s just too much,” one volunteer said.

The consequences are painfully real. Residents who applied for jobs or health certificates were sometimes told they had “failed” their medical exams because their lungs showed signs of heavy smoking—even if they had never touched a cigarette.

“A man told me that he took his daughter, a young daughter, to the hospital, and the doctor told him his daughter is a smoker,” shared Weyinmi Okotie, GAIA’s Clean Air Program Manager for Africa.

“Because [those people] live in Ogijo, everybody is tagged as smokers,” he added.

Okotie described the local frustration: “People of Ogijo still live in that community, drowning in air pollution.”

(Part 2: The next chapter: turning hard-won data into real change and accountability.)

(2025/07/16-10:21)

To read a full story, please click here to find out how to subscribe.

INQUIRER

- 07/16 13:59 OVP says Sara Duterte ‘eager’ to face impeachment raps

- 07/16 13:46 Peso falls to 57 level as dollar gains on bets of less dovish Fed

- 07/16 12:54 OVP reports 34% utilization rate for 2025 budget amid challenges

- 07/16 11:38 West PH Sea: PH OKs US plan to build boat facilities in 2 Palawan areas

- 07/16 10:21 Clearing the air: Ordinary citizens uncover toxic truths near waste incinerators

- 07/16 09:30 Lucio Co-led The Keepers buys 50% of Sula liquor maker

- 07/16 02:04 BSP wants equal rules for hybrid, purely digital banks

- 07/15 17:47 BI nabs 4 Chinese nationals for illegal employment

- 07/15 12:02 Marcos’ trust rating up by 10 points, reaching 48% in June – SWS

- 07/15 10:35 Remittance growth in the Philippines slowed to 2.9% in May

- 07/15 09:57 DMW eyes safeguards for OFWs in Oman

- 07/15 09:09 Real problem in Metro Manila roads: Lack of PUVs equals overloading

- 07/14 13:13 PH experts: Chinese ship damages Pagasa corals with parachute anchor

- 07/14 12:55 Rejoining ICC not in motion, but discussed – DFA

- 07/14 11:19 Marcos wants to open PH more to world to boost tourism, economy

- 07/14 08:39 Lacson files bill seeking to expand coverage of Anti-Wiretapping Act

- 07/14 08:22 BSP wants daily limits to online gambling payments

- 07/14 05:20 Duterte’s lawyers question ICC jurisdiction – again

- 07/14 02:08 PSA: Domestic rice output grew in Q2

- 07/14 02:04 Philippine sugar bound for US seen spared from new tariffs

- 07/13 10:35 Rubio to China: Abide by 2016 arbitral ruling on West Philippine Sea

- 07/13 02:14 Filipinos to deliver remote patient care

- 07/11 11:41 PH, Australia to resume biennial military drills in August – envoy

- 07/11 11:34 Palace confirms Marcos will fly to US for a bilateral meeting with Trump

- 07/11 09:35 Legarda, Hontiveros renew push for blue economy: Make it a priority

- 07/11 05:42 Chinese trader Tony Yang arrested for second time

- 07/11 05:34 Pagcor orders removal of e-gambling billboard ads, to limit TV promos

- 07/11 02:28 Trump tariff feared to spoil FDI momentum

- 07/11 02:26 Metro Manila needs 3 years to stabilize residential glut - Leechiu

- 07/11 02:22 200-MW wind park to rise in Cavite

- 07/10 14:16 Marcos orders aid for PH seafarers’ kin after vessel sinks in Red Sea

- 07/10 13:23 NMESIS deployed during drills, but no missiles fired, spox clarifies

- 07/10 12:23 FDI net inflow rises 7.1% in April

- 07/10 11:46 DTI raises concern about 20% US tariff on Philippine exports

- 07/10 09:30 Palace okay for Philippines’ first hydrogen deals keenly awaited

- 07/10 09:09 Philippine delegation heads to US to negotiate tariffs

- 07/10 08:43 Marcos offers sympathies to Trump, Americans over Texas floods

- 07/10 05:46 Fintech firms agree to tighten e-gambling ‘safeguards’

- 07/10 02:02 Unlike most peers, Philippines seen to benefit from US tariff concessions

- 07/09 16:59 Palace: No Filipinos affected in Texas flash floods

- 07/09 13:56 Philippines clears more sugar imports to stabilize prices

- 07/09 13:17 Palace to Sara Duterte: Every public servant should assess themselves

- 07/09 12:57 Rodrigo Duterte tells Sara: Cremate me in The Hague if I die here

- 07/09 11:58 Leonen tells jail officials: Justice must restore, not just punish

- 07/09 11:51 DILG: Over 10,000 inmates finish basic education in jail through ALS

- 07/09 10:00 Pampanga's SGH bags sole right to develop Best Western hotels in Philippines

- 07/09 02:07 Factory output growth rises to 10-month high

- 07/09 02:05 Bank lending sustains double-digit growth amid interest rate cuts

- 07/08 14:54 DMW: 2 ships with 38 Filipino seafarers attacked near Yemen

- 07/08 14:05 China ship presence in PH waters hits record high in June – Navy

- 07/08 13:46 Pagcor wants tighter control, not total ban, on online gambling

- 07/08 13:37 Teodoro on transfer of Japanese destroyers: Depends if they fit fleet

- 07/08 12:07 Lazaro meets with Asean secretary general for PH's 2026 chairship

- 07/08 10:49 Del Monte Philippines grows sales to P44.2B

- 07/08 10:18 Gatchalian files bill to prevent Philippine citizenship fraud

- 07/08 09:56 Philippines' unemployment rate dropped to 3.9% in May - PSA

- 07/08 02:12 Almost 60% of Philippine retail payments now digital

- 07/08 02:10 Philippines ramps up efforts to forge win-win US trade deal

- 07/07 23:36 US fighter aircraft F-35 joins PAF patrol to mark annual air drills

- 07/07 13:43 BI uncovers trafficking of Filipinos to Pakistan for online gaming jobs

- 07/07 11:36 High costs, unclear rules stall waste-to-energy growth, says business group report

- 07/07 11:06 Ejercito calls for stricter regulation of online gambling

- 07/07 09:32 Bising, habagat affect over 27,000 families across Luzon – NDRRMC

- 07/07 02:09 Philippines' credit card debt reaches ‘critical risk’ levels

- 07/07 02:03 DigiPlus’ success attracts big players to gaming scene

- 07/06 22:27 PH Navy to inspect Japanese warships before ‘possible transfer’

- 07/06 05:32 China hit for trying to block West Philippine Sea documentary

- 07/06 02:00 Let there be light: Agusan school taps solar energy

- 07/04 11:31 2 ex-Pogo workers nabbed in Las Piñas for selling fake money worth P150,000

- 07/04 09:52 ICC prosecutors strengthen case vs Duterte with 11th batch of evidence

- 07/04 08:21 Marcos eyes new fish ports, ice plants to cut costs for fisherfolk

- 07/04 05:50 Inflation, job security temper Filipinos’ optimism about 2026

- 07/04 05:34 Poll observers from EU note socmed misuse, ‘outdated’ laws

- 07/04 05:30 Putting ‘limits to gaming access’ is an option – BSP

- 07/04 02:30 Gov’t debt rose to new record high of P16.92T

- 07/04 02:20 SEC eyes enhanced REIT framework

- 07/04 02:18 Shakey’s rides growth wave, expands to Laos, Taiwan

- 07/03 16:06 Palace vows to raise PH economy to upper middle-income bracket

- 07/03 15:31 BSP gears up to protect Filipinos vs danger from online gambling

- 07/03 15:11 Anti-terror law’s purpose not achieved five years on – lawyers

- 07/03 09:48 West PH Sea: PAF proposes purchase of ‘flying radars’ amid woes

- 07/03 05:34 ‘Genuine’ Filipinos won’t cower before China, says Malacañang

- 07/03 05:04 Baguio execs renew bid to collect P200M in John Hay revenue

- 07/03 02:20 Aboitiz Power keen on scaling up solar capacity

- 07/02 17:11 7 Chinese nationals arrested in Pampanga for telecom fraud

- 07/02 13:40 Palace: Harry Roque’s remark on his PH departure is ‘barber’s gossip’

- 07/02 13:06 Del Monte Foods seeks US bankruptcy protection, asset sale

- 07/02 11:26 Peza clears P72B investments in 1st semester

- 07/02 08:02 Philippines remains stuck in lower middle-income group

- 07/02 05:25 Smuggled onions, mackerel worth P34M seized at Manila port

- 07/02 04:30 SC issues writ of kalikasan vs Samal-Davao bridge project

- 07/02 02:11 Philippine factory activity recovered in June

- 07/02 02:08 More int’l flights coming to Manila, says Naia operator

- 07/02 02:02 P1-B budget sought to start corn procurement program

- 07/01 14:32 Marcos weighing public sentiment on PH return to ICC – Palace

- 07/01 13:10 China bars ex-senator Tolentino from entering its territories over WPS stance

- 07/01 12:22 Bill to set public school teachers' minimum wage at P50,000 refiled

- 07/01 11:53 Smuggled agri products worth P34M seized

- 07/01 11:26 PSE approves Keppel Philippines delisting on July 8

- 07/01 09:50 Teodoro: Time for PAF to have airborne early warning, control system

- 07/01 05:45 Study: WPS, Benham Rise world’s soft coral hot spots

- 07/01 04:40 Fishers’ group rejects US ammo factory in Subic Bay

- 07/01 02:14 Fuel discounts for PUVs launched amid rollback

- 07/01 02:13 BSP still sees below-target June inflation despite oil price spike

- 06/30 17:04 Teodoro on US-proposed Subic ammo plant: It's ‘definitely encouraged’

- 06/30 13:08 Philippines, Lithuania sign defense pact amid West PH Sea challenges

- 06/30 09:27 Senate open to proposals to improve public access to budget process

- 06/30 05:55 Manila court: Alice Guo ‘a Chinese national’

- 06/30 05:45 Village halls in Albay’s Ligao City go solar

- 06/30 05:35 MMDA completes switch to adaptive traffic lights

- 06/30 02:08 Airlines in Asia-Pacific see turbulence ahead

- 06/30 02:07 Higher deficit ceiling forces tweaks to Philippines' borrowing plan

- 06/30 02:06 MVP awaits big buyers, steady market for Maynilad IPO

- 06/27 11:26 DILG: Paralegal aid frees nearly 68,000 detainees to ease jail crowding

- 06/27 11:08 Subic-Clark-Manila- Batangas cargo railway gets technical aid from USTDA

- 06/27 10:44 Filipinos in Hawaii urged to get US citizenship amid ICE crackdown

- 06/27 09:46 2 Chinese arrested for shooting at Filipino in Makati City

- 06/27 05:48 Escudero, Romualdez likely to keep top posts

- 06/27 05:30 Cayetano warns vs rushed dismissal of impeachment raps

- 06/27 02:34 Marcos gov't cuts 2025 growth outlook on the Philippines

- 06/27 02:30 Gov’t back to budget deficit in May, but smaller

- 06/27 02:18 AboitizPower launches P30-B retail bond offer

- 06/27 02:10 AI-enabled commerce coming soon to digital store near you

- 06/26 15:05 DTI: Prices of basic goods remain stable amid global risks

- 06/26 14:55 Palace hits back after Sara Duterte defends ‘personal’ Australia visit

- 06/26 12:28 Fisherman finds P166.6-M drugs at sea, turns them over to PDEA

- 06/26 10:48 ALI, Globe land on TIME’s list of sustainable companies

- 06/26 05:36 DOJ eyes Japan tech in search for missing cockfighters

- 06/26 05:32 House prosecutors submit Sara Duterte impeach complaint certification

- 06/26 05:30 DOJ heeds ICC ‘request’ to assist witnesses

- 06/26 04:30 From mangroves to meals

- 06/26 02:28 BSP: Number of fake banknotes surged by 18.4% in 2024

- 06/26 00:19 DFA launches book promoting PH Studies programs abroad

- 06/25 17:00 Peso strengthens to 56:$1 as Middle East optimism weakens dollar

- 06/25 16:04 West PH Sea: Recent US-PH-Japan sea drills viewed as ‘counter-China’ effort

- 06/25 13:10 Pope Leo XIV appoints Br. Armin Luistro to Vatican dicastery

- 06/25 13:00 PNP-ACG: Most online scammers now are Filipinos who ‘learned’ from Pogos

- 06/25 11:47 Romualdez: House commits to fund thousands of new teaching posts

- 06/25 10:42 Marcos: No need for fuel subsidy talks as prices have not risen

- 06/25 05:55 Duterte rant, partner Avanceña’s rage cited to block his release

- 06/25 05:45 AFP battle staff readies plans amid Middle East tensions

- 06/25 02:09 Faster 5.6% Philippine GDP growth seen in Q2

- 06/25 02:02 BSP wants banks to adopt model risk management

- 06/24 14:12 Chinese submersible drones’ sinister roles in expansionism

- 06/24 13:33 AFP ready to aid gov't in repatriating Filipinos in Iran, Israel

- 06/24 09:19 31 Filipino repatriates from Middle East now safe – DMW

- 06/24 08:29 Padilla seeks Duterte repatriation, but Senate rejects his resolution

- 06/24 02:10 Philippine peso, stocks feel pressure of world on edge

- 06/24 02:08 Middle East war may cut short BSP easing, say analysts

- 06/24 02:03 Offshore wind projects get boost as Philippines launches road map

- 06/24 02:01 Philippines linking rural farms to markets via steel bridges

- 06/23 13:35 More than 100 Filipinos in Israel lost their homes – PH embassy

- 06/23 11:47 Panfilo Lacson says US bombing of Iran nuke sites could start world war

- 06/23 05:50 Over 200 Filipinos in Israel, Iran seeking repatriation

- 06/23 05:20 Carpio: Sara Duterte risks waiving rights without response to court

- 06/23 02:10 Philippine banks cut property exposure to lowest in 6 years

- 06/23 02:08 Property firms endure condo glut

- 06/23 02:07 Likely better harvest lessens rice imports

- 06/22 05:32 Next week’s fuel price hike seen exceeding P5 per liter

- 06/21 18:07 Marcos: ‘We did not yield’ on West Philippine Sea issue

- 06/20 14:42 Sara Duterte may be violating obligation with her trips abroad – Palace

- 06/20 12:51 Marcos meets Japanese tourism partners on 2nd day of Japan trip

- 06/20 11:29 Sara Duterte on personal trip to Australia to join rally for her father

- 06/20 08:58 DOTr studying train line upgrades – Dizon

- 06/20 05:32 UN rapporteur urges PH to return as ICC member

- 06/20 04:00 Philippine conglomerates increase investments in health care

- 06/20 02:20 AGI eyes new luxury hotel, malls through P59-B buildout

- 06/20 02:16 Robinsons Land pumps up REIT arm with 9 more malls

- 06/20 02:10 Preparing Philippine businesses for sustainability compliance

- 06/19 17:59 Torre to police commanders: ‘Don’t hide in your offices’

- 06/19 14:22 New COVID-19 'Nimbus' variant not yet detected in PH, says DOH chief

- 06/19 12:07 Killing of P200 pay hike bill also kills bid for living wage

- 06/19 11:40 7 Filipinos hurt in Iran missile strikes on Israel – PH embassy

- 06/19 11:08 Meralco unit PacificLight switches on 100-MW plant in Singapore

- 06/19 09:56 PH peso sinks back to 57:$1 as US Fed hold boosts dollar

- 06/19 05:12 Barbers pushes for AI-regulating gov’t agency

- 06/19 02:22 DTI launches supply chain, logistics center to support MSMEs

- 06/19 02:18 Firms in Spain earn nod to send meat to the Philippines

- 06/18 16:51 PSEi retreats as Israel-Iran conflict rises

- 06/18 12:25 Motorists will get fuel subsidies due to Mideast tension – Marcos

- 06/18 09:15 Zero dengue deaths by 2030 possible – scientific working group

- 06/18 08:54 Experts urge PH gov't to expedite approval of new dengue vaccine

- 06/18 02:16 Gov’t orders DOE to ensure sufficient oil supply

- 06/18 02:13 Philippines to adopt OECD cryptocurrency tax framework

- 06/18 02:10 New incentives program for electric vehicles seen ‘more inclusive’

- 06/18 02:09 San Miguel leads Philippine firms in ‘Southeast Asia 500’ list

- 06/18 02:04 Philippine exit from list of ‘risky’ markets seen raising investor interest

- 06/17 13:12 MMDA: Driver caught 309 times for same traffic violation in 10 months

- 06/17 12:00 DOTr chief commits privatization of 10 airports by 2028

- 06/17 10:49 House refusal to accept Duterte lawyers’ entry may delay trial – Senate

- 06/17 07:01 Philippines climbs to 51st in global competitiveness report

- 06/17 05:45 Filipina worker wounded in airstrikes vs Israel ‘critical’